Dodgy Ducts Dispute In F1

Rear brake ducts might seem trivial to a Formula One fan but they are a very big deal right now in the grand prix pitlane.

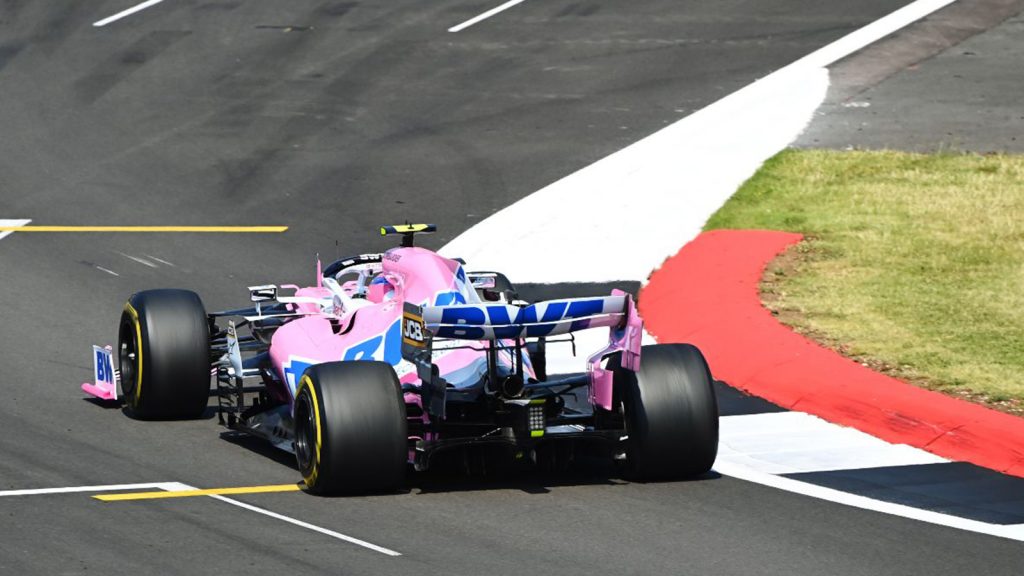

The dodgy ducts are on a Racing Point, a car variously described as the ‘Pink Mercedes’ and ’Tracing Point’, and are causing a fair amount of upset in F1 circles.

Very few people seem to understand the arguments involved in the case, but the billionaire boss of Racing Point says he is “extremely angry” after protests, an FIA ruling, and appeals by rival teams.

“I am extremely angry at any suggestion we have been underhand or have cheated – particularly those comments coming from our competitors. These accusations are completely unacceptable and not true,” Lawrence Stroll says.

“My team has worked tirelessly to deliver the competitive car we have on the grid. I am truly upset to see the poor sportsmanship of our competitors.”

The brake duct situation is a Very Big Deal to teams posturing over the future regulations for Formula One, but very few people outside the garages even understand what is happening, or what the ducts are and what they do.

Renault protested Racing Point at the Styrian, Hungarian and British GPs and alleged its RP20s used front and rear brake ducts which were based on, and near-identical to, the same parts from the 2019 Mercedes W10.

Renault’s contention was that the parts had not been designed by Racing Point. The challenge was not against the whole car but was specifically related to the brake ducts because these were what are called ‘non-listed’ parts in 2019, which means that teams could buy the parts or technical drawings from a rival team.

However, because it was felt that these parts had a very significant impact on the aerodynamics of a car they should be built by each individual team. So they became ‘listed’ parts in 2020.

Racing Point argues that, although the shape of the brake ducts is identical to the W10, this did not mean that the parts had not gone through a design process. They said there is no definition of “design” in the F1 Sporting Regulations and that the parts had been through a detailed – and documented – design process.

But the team had failed to find a better configuration and so had left the parts the same as they were, although Mercedes had only provided the shape of the parts (which was allowed) but did not give any details about how such parts could be manufactured or what materials would be required.

The FIA Technical Department said that it did not believe that the definition of design used by Racing Point was broad enough and ought to have given more importance to the original shape of the parts that the team bought from Mercedes, at the point at which such an arrangement was acceptable. The Technical Department also felt that the change of status was agreed in April 2019 and that Racing Point knew that it needed to design its own brake ducts.

However, as one cannot un-learn what they know, there is a solid argument that Racing Point designed exactly the same components because they could not improve on the original.

This was an interesting argument and the FIA Technical Department did not fully agree with this, but accepted that they had not provided any specific guidance or clarification on how the transition from unlisted parts to listed parts should be managed.

They also admitted that when the FIA inspectors visited Racing Point in March there was no specific discussion about the brake ducts.

In addition, the team was entirely open and transparent because the engineers believed that the parts were compliant with the regulations, based on their definition of design.

It was also noted that Racing Point had not been challenged on the rest of the car because the FIA had concluded that there was no reasonable objection, as the chassis had clearly been reverse-engineered, rather than being duplicated.

The FIA put together a panel of F1 Stewards at Silverstone – to which no-one objected – to hear the arguments and chose a group that was well-qualified in legal, engineering and procedural terms.

The panel included Gerd Ennser, a doctor of law who has been both a prosecutor and a judge in Bavaria and has also a huge amount of experience as an F1 steward, dating back to 10 years.

He was joined by Dennis Dean, a member of the FIA World Motor Sport Council. An engineer by training and a career officer in the US Navy, Dean has been a motor racing official for more than 40 years.

The other two members of the panel were Austria’s Walter Jobst and Britain’s Richard Norbury – both members of the national motorsport courts of appeal in their respective countries. Norbury is also chairman of the UK Motor Sports Council’s Judicial Committee.

The Stewards heard the various parties and concluded that, although the rules were ambiguous, design requires a broader definition than that applied by Racing Point and that the design work inherent in a part must be taken into consideration and thus concluded that the ducts had been principally designed by Mercedes.

They made the point that, as the ducts were compliant with the 2020 rules, it was not realistic to expect Racing Point to re‐design or re‐engineer them in a way that would effectively require the team to unlearn what they already knew.

The panel specifically pointed out that the breach was about the F1 Sporting Regulations and not at all the same as non-compliance with the Technical Regulations. Nonetheless they felt that there had been an infringement in the design process and it should be penalised.

They ruled that the penalty imposed ought be sufficient to cover the potential advantage gained for the entire season, which meant that the team could continue to use the parts in question, as they had been punished. The team received a reprimand, the loss of 15 points and a fine of $657,000. The drivers were not sanctioned.

But the dispute did not stop with the FIA ruling and the penalty.

Some teams believe that the definition of ‘design’ needs to be refined and the sport must decide what philosophy it wants to adopt.

There are benefits for all the teams from having some parts that can be sold – saving the small teams development costs and providing big teams with revenues – but the FIA believes that F1 cars should not all look the same and that there needs to be a regulatory framework to suit the modern technology available for measuring and copying.

“I think there are areas that this process demonstrated to us that certain aspects of the rules were not completely clear and that basically a big debate was had about what really is a design and what happens when pieces change status,” says Nicholas Tombazis, who oversees single-seater technical issues for the FIA.

“The stewards took the view that as it was the process that was at fault, not the components themselves and they applied the sanction of championship points and a financial sanction. But they deemed that the sanction covered all the issues with the process and therefore while in subsequent races the protest was accepted as justified, they felt it did not require further sanction.”

“Copying has been taking place in F1 for a long time. People take photos and sometimes reverse-engineer them and make similar concepts, and in some cases make identical or close-to-identical concepts.

“We don’t think this can stop completely in the future. What we do think is that Racing Point took this to another level.

“They clearly decided to apply this philosophy for the whole car by doing what I would call a paradigm shift. They actually used a disruption in the process that has been the norm in designing a Formula 1 car for the last 40 years.

“One should not penalise them for that because they were original in deciding to follow this approach. However, we do not think that this is what F1 should become.

“We don’t want next year to have eight or 10 copies of the Mercedes on the grid , where the main skill becomes how you do this process. We don’t want this to become the norm of F1 and we do plan to introduce some amendments to the 2021 Sporting Regulations that will prevent this.”

The report produced by the panel, which ran to 14 pages, was a document that explained, with impressive clarity, that the cars were legal, but some of the team bosses, notably McLaren’s Zak Brown, seemed rather ill-informed when responding.

Having referred to the cars as being “illegal”, Brown went on to suggest that the argument that the Racing Point RP20 was reverse-engineered from photographs was “BS”, which ignored the findings of the FIA Technical Department and the Stewards. It upset Racing Point and Mercedes – McLaren’s future engine supplier – was none too impressed.

Lawrence Stroll was hugely emotional when he spoke at Silverstone about the ducts, the penalty, and rival team bosses.

“I understand that the situation in which the FIA finds itself is difficult and complicated for many reasons, but I also respect and appreciate their efforts to try and find a solution in the best interests of the sport,” he says.

Even so, Renault, McLaren, Ferrari and Williams have all announced the intention to appeal the decision.

And so it escalated to another level, with Stroll saying they are “dragging our name through the mud and I will not stand by nor accept this.”